What Is Green Celadon?

What is Celadon?

Celadon is a type of porcelain that is known for its distinctive green glaze. The term “celadon” comes from the French word for the grey-green color of the glazes used on this pottery (source). Celadon originated in China during the Eastern Han dynasty (25-220 CE) and further developed during the Three Kingdoms period (220-280 CE). It reached the height of popularity during the Song and Yuan dynasties of China (960-1368 CE).

The technique of creating celadon spread from China to Korea and Japan. Korean celadons from the Koryo dynasty (918-1392) and Japanese celadons from feudal Japan (1185-1868) are especially prized. Celadon production flourished because the glazes could complement the locally available clay bodies. Master potters guarded the secret techniques that allowed them to create the unique jade-like color and crackled surface (source).

Part of celadon’s appeal is the wide range of colors that can be achieved, from pale green to deep blue-greens. The glazes pool and drift during firing, creating unique patterns and emphasizing the graceful shapes of celadon vessels. Celadons are admired for their aesthetic beauty as well as their rarity and antiquity.

Celadon Glazes

Celadon glazes are known for their distinctive sea-green colors, which have a tranquil and elegant appearance reminiscent of jade. The secret to achieving this color lies in the glaze composition and firing techniques used. Celadon glazes consist of a feldspathic mineral body combined with clay and small amounts of iron oxide. Bamboo ash is also commonly added, providing potassium and silica which enhance the glaze’s translucency and promote the desired sea-green tones.

During firing, the iron oxide undergoes several color transformations as the temperature changes before settling into the final blue-green hue. The translucent, glass-like quality of celadon glazes results from firing to high temperatures between 2,372-2,552°F (1,300-1,400°C), which causes the glaze to melt and pool thinly over the clay body beneath. Specific firing techniques like reduction firing (limiting air flow) help accentuate the greenish-blue color. The final result is a smooth, pale green glaze renowned for its resemblance to ancient Chinese jade.

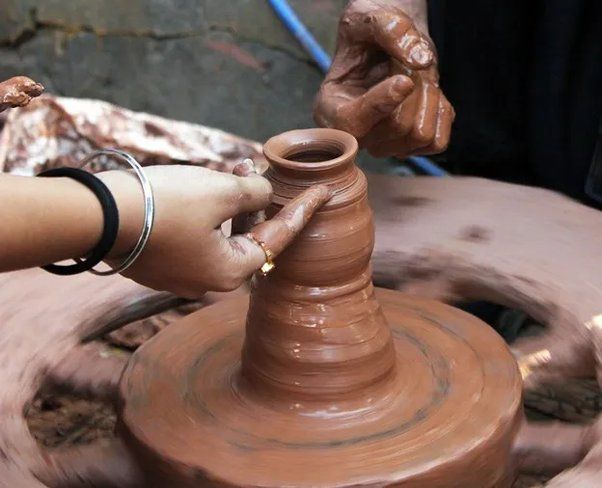

Celadon Production

Celadon has historically been produced in several main production centers in East Asia. Two of the most significant are Longquan in China and Buncheong in Korea.

Longquan was one of the main celadon production areas during the Song dynasty in China. Located in Zhejiang province, Longquan celadon utilized local clay sources and firing techniques to produce the distinctive green-glazed ceramics. Longquan celadons were highly prized and traded widely across East Asia and beyond. According to some scholars, Longquan celadon production declined in the late 14th century.

Buncheong wares emerged as a major ceramic type during the Joseon dynasty in Korea starting in the 15th century. Buncheong often imitated Longquan celadon forms and designs, but utilized white slip decorations and impressed designs rather than green glazes. Buncheong bowls and other vessels were widely produced and used during this period in Korea.

Today, celadon continues to be produced in Korea, China, Japan and other areas, often drawing inspiration from classic Longquan and Buncheong wares. Modern vessels include vases, bowls, dishes, boxes and figurines. Decorative techniques range from carved designs to inlaid appliqués to painted motifs under the glaze.

Notable Examples

Some of the most famous and notable celadons throughout history have been designated national treasures in Korea and China. For example, according to the Wikipedia page on Celadons (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Celadon), “Three pieces originally from China have been registered by the government as national treasures. They are two flower vases from the Longquan kiln dating to the Yuan dynasty, under Kublai Khan and a Green-Glaze Incense Burner from the Jin dynasty.”

Excavations of ancient tombs have also uncovered stunning and valuable celadon pieces. As described in the Met Museum’s essay on Goryeo Celadon (https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/cela/hd_cela.htm), “Perhaps the most celebrated examples of Korean celadons are those recovered from the twelfth-century tomb of the Goryeo crown prince in Yangju, Kyŏnggi Province. The tomb yielded about two hundred celadon vessels, including flasks, cups, bowls, and pitchers. The eleventh-century tomb of King Munjong in Kongju, Ch’ungch’ŏngnam Province, contained over seven hundred celadons.”

These discoveries provide invaluable information about the skill of ancient celadon artisans as well as the esteem and value placed on fine celadon wares throughout history.

Celadon Trade

Celadon wares were widely traded along both overland and maritime Silk Road trade routes during the 10th to 14th centuries. Chinese celadons were eagerly sought after across Asia and the Middle East for their smooth green-blue glazes and refined forms. Korea also became an important exporter of quality celadons from the 12th to 14th centuries, with abundant deposits of quality clays and feldspar ideally suited to celadon production.

Major export celadon production centers developed in China at Longquan in Zhejiang province and at Yaozhou in Shaanxi province. Vast quantities of celadon wares were shipped from China across the maritime trade routes reaching as far as Southeast Asia, the Middle East, and East Africa (Economy and Trade | Silk Roads Programme). Korean celadons from the Koryŏ dynasty were also traded through maritime networks, spreading the popularity of the green-glazed ceramics.

High quality celadons were regarded as luxury goods, purchased by elites, temples, and the upper classes across Asia. The ceramics were sometimes gifted as diplomatic offerings, spreading celadon prestige and fame. As celadon techniques spread, local potteries tried to emulate the glazes and forms, fueling further demand for the genuine exported wares. Celadons played a key role in transmitting ceramic technologies and artistic motifs between China, Korea, Japan and Southeast Asia along the far-reaching Silk Road trade networks.

Celadon Collecting

Celadon wares from the Song dynasty (960-1279) are among the most prized and valuable for collectors. Pieces from the Ru and Guan kilns often fetch high prices at auction, such as the Ru tea bowl from the 11th century that sold for over $30 million at a Christie’s auction in 2019 (Christie’s). The glaze color, designs, thickness, and quality of craftsmanship all impact the value of celadon pieces.

Rarity also plays a major role. Celadons from the Yaozhou kilns of the Song dynasty, for example, are more scarce than Ru wares, driving prices up. Condition is another key factor – only the finest quality celadons in pristine condition will reach top dollar values at auction. Cracks, chips, or repairs will negatively affect value.

Later celadons from the Ming and Qing dynasties can also command high prices, especially imperial pieces. A Ming dynasty celadon-glazed vase sold for over $10 million at a Christie’s auction in Hong Kong in 2022 (TheValue). Provenance and authenticity documentation boost value for collectors as well.

Celadon Imitations

Later Japanese potters and European potters attempted to recreate the prized celadon glazes of ancient Chinese and Korean celadon wares. However, reproducing the exact techniques and achieving the same jade-like colors proved incredibly difficult.

One challenge was recreating the clay body composition and achieving the right level of iron oxide content, which gives celadon its distinctive greenish-blue hues. The ancient Chinese potters had perfected specific clay mixtures and firing methods tailored to celadon production.

The firing process was also difficult to reproduce. Celadon requires firing at very high temperatures of 1,250–1,300°C in a reduction atmosphere. This needs precise control over oxygen flow in the kiln. The ancient ceramists had mastered the ability to regulate oxygen perfectly to create the desired colors and effects.

Later imitation celadons often have a more grayish, duller hue compared to ancient celadons. Examining the glaze color and quality provides clues to distinguish real ancient celadon from later imitations. Marks and provenance can also authenticate real celadon wares.

While imitation celadons may lack the brilliance of true ancient celadons, they remain artistically and historically significant in their own right.

Celadon in Art

Korean celadon glazes and aesthetics have profoundly influenced modern ceramic art and design. The vibrant jade-green colors and delicate cracked patterns achieved in ancient Korean celadon gained worldwide acclaim. As early as the 1920s, modern potters like Bernard Leach studied Korean celadons and adapted celadon glazing techniques in their studios (See the article, Goryeo Celadon, from The Metropolitan Museum).

Today, many contemporary potters create artworks and functional wares inspired by the celadon tradition. The influence is seen in the use of celadon glazes, shapes like the bottle and box forms popular in 12th century Korea, stamped designs, inlaid slip decoration, and more (Source: Korean Celadons of the Goryeo Dynasty). Modern artists also adapt celadon glazing techniques by combining them with other regional traditions.

Beyond pottery, celadon colors and designs also appear in glass, lacquerware, jewelry, textiles, and other media. The vibrant hues and cracked patterns have become icons of Korean artistry. Some designers use celadon finishes in furniture or architecture as well. Celadon continues to represent the pinnacle of Korean ceramic achievements and remains an inspiration for artists today.

Celadon Techniques Today

Though celadon production declined after the Joseon dynasty, artisans today are keeping the ancient traditions alive and innovating new glaze effects and vessel forms. Many modern ceramists create work inspired by celadon’s long history while giving it a contemporary twist.

Notable Korean ceramists like Yi In-sang have mastered the difficult technique of inlaying designs in colored clay beneath translucent green glazes. This shows the staying power of traditional celadon aesthetics in modern artistry. Other artists use celadon glazing techniques on new forms like abstract sculptures.

Advancements in kiln technology have also expanded the possibilities of glaze effects. The traditional reduction firing method is still favored by many artisans, but some also incorporate oxidation into parts of the firing cycle to alter colors and textures.

While much celadon today emulates old styles, there are also novel approaches involving new shapes, unconventional carved designs, and an expanded color palette. Contemporary celadon celebrates connections to history while advancing into the future.

Conclusion

Celadon glazes produce a distinct pale green hue that has been prized across Asia for over a thousand years. The unique color comes from iron oxide in the glaze reacting to the reducing atmosphere of the kiln. Celadon originated in ancient China and spread via trade routes to Korea, Japan, and Southeast Asia.

Some of the most famous and coveted celadons were produced in China during the Song dynasty and in Korea during the Goryeo dynasty. The delicate beauty of celadon ceramics made them objects of trade and diplomacy, while also developing as art forms in their own right. Celadon glazes require precise control of materials, firing conditions, and techniques. Their subtlety of color, pleasing forms, and the technical mastery involved contribute to the enduring appreciation of celadon wares.

Today, celadon production continues, often drawing inspiration from classic examples. Both master potters and hobbyists work to reproduce the luminous hues of ancient celadons. The legacy of celadon serves as a constant reminder of the creativity and ingenuity of potters across generations. While fashions and styles may change, celadon glazes still enchant audiences today just as they did centuries ago. The allure of their soft, sea-green tones is a testament to humankind’s enduring affinity for beauty.