Who Is Henry Clay And Why Is He Important?

Early Life and Education

Henry Clay was born on April 12, 1777 in Hanover County, Virginia to Reverend John Clay and Elizabeth Hudson Clay. He came from a family of Baptist ministers and Clay had five surviving siblings (history.state.gov). Clay had a minimal formal education as a child. However, he later read law under the tutelage of George Wythe, was admitted to the Virginia bar in 1797, and gained admission to the Kentucky bar that same year where he set up a law practice in Lexington (britannica.com).

Entry into Politics

Henry Clay first entered politics when he was elected to the Kentucky House of Representatives in 1803 at the age of 26 [1]. He quickly rose to prominence as Speaker of the House and helped lead the party that opposed Kentucky’s first governor. Clay served in the Kentucky legislature until 1806 when he was elected to the U.S. Senate at the age of 29 to fill an unexpired term [2].

Clay served multiple terms in the U.S. Senate between 1806-1807, 1810-1811, and 1831-1842. As senator, he advocated for protectionist trade policies and was a leading supporter of the War of 1812. He also strongly defended national sovereignty and opposed European interference in the Western Hemisphere.

Clay’s most significant leadership role was as Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives. He was elected Speaker on his first day in the House in 1811 and held that position from 1811–1814, 1815–1820, and 1823–1825, the only person to hold the office for 10+ years until Sam Rayburn in the 20th century [3]. As Speaker, Clay helped guide the nation’s policies as the U.S. faced its first major economic crisis and waged the War of 1812 against Britain.

Key Legislation

As a leading member of Congress, Henry Clay was instrumental in formulating and passing several key pieces of legislation in the early 19th century. Three of his most significant legislative achievements were the American System, the Missouri Compromise, and the Compromise Tariff of 1833.

Clay was a proponent of the American System, a program for economic development that called for protective tariffs, a national bank, and federal funding for infrastructure projects like roads and canals. As Speaker of the House from 1811–1814, 1815–1820, and 1823–1825, Clay pushed through legislation enacting parts of this system, believing it would strengthen the young nation’s economy and ensure its independence (Henry Clay – People).

In 1820, Clay brokered the Missouri Compromise, which regulated slavery in the western territories and temporarily diffused tensions between northern and southern states. It admitted Missouri as a slave state and Maine as a free state, maintaining the balance in Congress, and prohibited slavery north of 36°30′ latitude in the Louisiana Territory (Henry Clay: A Featured Biography).

To quell the Nullification Crisis over protective tariffs, Clay engineered the Compromise Tariff of 1833, which gradually reduced tariffs over 10 years. This compromise helped preserve the Union and stave off potential conflict between federal and state governments (Henry Clay).

Presidential Ambitions

Clay ran for president a total of three times – in 1824, 1832, and 1844. However, he never achieved his goal of becoming president. In the controversial Election of 1824, Clay ran against John Quincy Adams, Andrew Jackson, and William H. Crawford. After no candidate received a majority of the electoral votes, the election was decided by the House of Representatives. Clay gave his support to Adams, who was chosen as president. This led to accusations of a “corrupt bargain” between Clay and Adams.

Clay ran again in 1832 as the candidate of the National Republican Party, but was solidly defeated by Andrew Jackson. Jackson saw Clay as the chief opponent of his policies during his first term, making Clay’s path to victory very difficult.

In 1844, Clay received the Whig Party nomination and ran against Democrat James K. Polk. The key issue was territorial expansion and annexation of Texas. Polk advocated the annexation of Texas and territorial gains from Mexico, while Clay opposed annexation over concerns it would add more slave states. Clay lost a very close race to Polk, who proceeded to deliver on his promises of expansion.

Clay’s inability to defeat two populist candidates in Jackson and Polk thwarted his presidential ambitions. However, his impact on national policy during his long tenure in Congress was still significant.

Opposition to Slavery

Though a slaveholder himself, Henry Clay opposed the spread of slavery into new territories and states. He argued that slavery was a “great evil” and called it “the darkest spot in the map of our country” (Smithsonian Magazine). In 1820, Clay helped author the Missouri Compromise which aimed to preserve the balance of power between slave and free states. He continued to speak out against the annexation of Texas in the 1830s and 1840s, fearing it would expand slavery and upset the balance (Henry Clay.org). Though a slaveholder, Clay believed slavery was morally wrong and hoped to limit its spread while gradually emancipating slaves.

Compromise of 1850

The Compromise of 1850 was Henry Clay’s last major effort to preserve the Union. As the debate over slavery and its extension into new western territories threatened to split the nation, Clay introduced a series of resolutions aimed at appeasing both North and South.

The Compromise brought California into the Union as a free state, allowed the New Mexico and Utah territories to use popular sovereignty to decide the slavery question, settled a Texas-New Mexico boundary dispute, abolished the slave trade in Washington D.C., and enacted a strict Fugitive Slave Law. Though controversial, Clay’s compromises staved off a potential secession crisis and war.

As Clay said in urging its passage, “I know no South, no North, no East, no West, to which I owe my allegiance.” His efforts were one final attempt to hold the Union together. According to the U.S. Senate, the Compromise of 1850 “brought Clay’s long career of brokerage to a close.”

Death and Legacy

Henry Clay died of tuberculosis in Washington D.C. on June 29, 1852 at the age of 75. He had spent most of his long public career serving as a Member of the House of Representatives, Speaker of the House, and Senator from Kentucky (U.S. Senate: Henry Clay Dies).

Clay left behind a legacy as a skilled negotiator and compromiser, earning him the nickname “The Great Compromiser.” He brokered important agreements like the Missouri Compromise of 1820 and the Compromise of 1850 to maintain unity between free and slave states. His ability to craft political deals and shape legislation cemented his reputation as one of the most impactful Congressional leaders in early American history.

Oratory Skills

Henry Clay was considered one of the greatest orators and most persuasive speakers of his time. He became known as the “Great Pacificator” and “The Great Compromiser” due to his eloquent use of oratory to broker compromises on several major national issues. Clay used his skills as an empathetic and charismatic speaker to build consensus between opposing viewpoints. His booming voice and dramatic gestures made him an electrifying speaker who could hold audiences spellbound for hours.

According to the Senate’s biography of Clay, “Throughout his long career, Clay’s oratorical skills made him a major power in Congress. His charm, wit, and blending of rational argument and dramatic fervor gave him rare persuasive powers in the chamber.” Clay put his oratory skills to work brokering legislative deals on divisive issues such as the Missouri Compromise of 1820, the Tariff Compromise of 1833, and the Compromise of 1850. His eloquence and forceful personality allowed him to keep the country from splitting apart over slavery leading up to the Civil War. While Clay’s compromises merely postponed the inevitable conflict, his oratory granted the young nation more time to grow stronger.

As a lawyer early in his career, Clay also used his public speaking abilities to successfully argue cases before juries. And later as a presidential candidate, he drew huge crowds who came to hear his legendary speechmaking. Clay’s oratory made him one of the most influential political figures of his era.

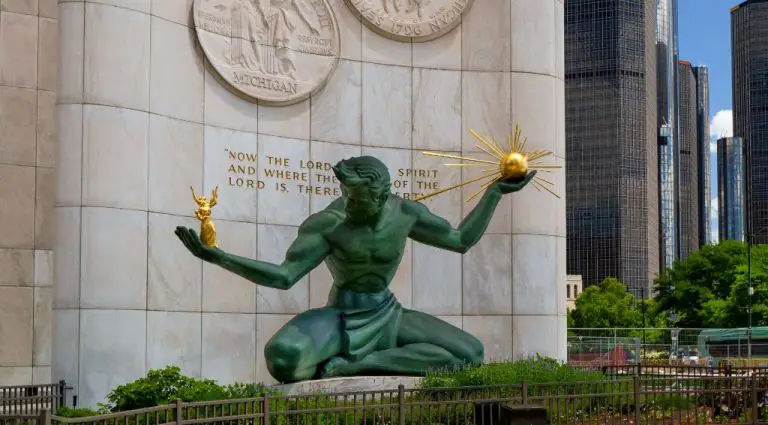

Monuments and Memorials

Henry Clay’s legacy has been memorialized through numerous monuments and places named in his honor. His most famous memorial is a statue in Washington D.C. depicting Clay standing in the U.S. Capitol building. The statue was commissioned in 1857, shortly after Clay’s death.

There are also several statues of Clay in his home state of Kentucky. A bronze statue stands in front of the Fayette County Courthouse in Lexington. The city’s main cemetery, Lexington Cemetery, features a towering monument dedicated to Clay at its center.

Over a dozen counties across the United States are named “Clay County” in honor of Henry Clay, including counties in Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Indiana, Kansas, Kentucky, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, North Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, and West Virginia.

Other places named for Clay include Clay, New York, Clay City, Kentucky, and Claysville, Pennsylvania. Several schools have also been named after him.

These widespread memorials and monuments testify to Clay’s enduring legacy and reputation as one of the most influential political figures of the 19th century.

Why Henry Clay Matters

Henry Clay was one of the most influential political figures in early 19th century America. As a Senator and House Speaker, he had an outsized impact on holding the Union together in the decades before the Civil War.

Clay was a major promoter of the American System, an economic plan based on protective tariffs, a national bank, and internal improvements. This program formed the basis for the Whig Party’s policies in the 1830s-1850s.

However, Clay’s most lasting legacy was in forging compromises on major sectional issues. With the Missouri Compromise of 1820, Clay helped defer the slavery question and maintain the balance of power between North and South. Three decades later, the Compromise of 1850 again kept the Union intact, thanks in large part to Clay’s efforts. Although the compromises were temporary solutions, Clay’s ability to craft deals acceptable to both sides set an important precedent in finding common ground.

According to Clay, “I’d rather be right than president.” While he never achieved his dream of becoming president, his lifelong work cementing political compromises was fundamental in holding the country together during the turbulent antebellum era. More than any other 19th century statesman before the Civil War, Clay’s legacy remains that of the “Great Compromiser.”