How The Terracotta Warriors Were Made?

The terracotta warriors are one of the most significant archaeological discoveries of the 20th century. They were created in China over 2,200 years ago to guard the tomb of the first emperor of China, Qin Shi Huang.

The warriors were buried with the emperor in 210–209 BCE when he died. His purpose was for these clay soldiers to protect him in the afterlife. There are over 8,000 life-size warrior figures, along with hundreds of horses and chariots.

They were discovered in 1974 by local farmers near the city of Xi’an in Shaanxi province, China. This extraordinary find gave the world a glimpse into the military power and artistic sophistication of ancient China.

The details and individuality of each warrior reveal the advanced pottery techniques and mass production capabilities during the Qin dynasty. They remain one of China’s most treasured cultural relics and are a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Clay Preparation

The terracotta clay used to create the warriors and horses was taken from nearby deposits around Xi’an. Potters carefully selected clay of the right consistency – neither too soft nor too hard. The clay needed to be soft enough to sculpt intricate details, yet hard enough to retain its form after firing.

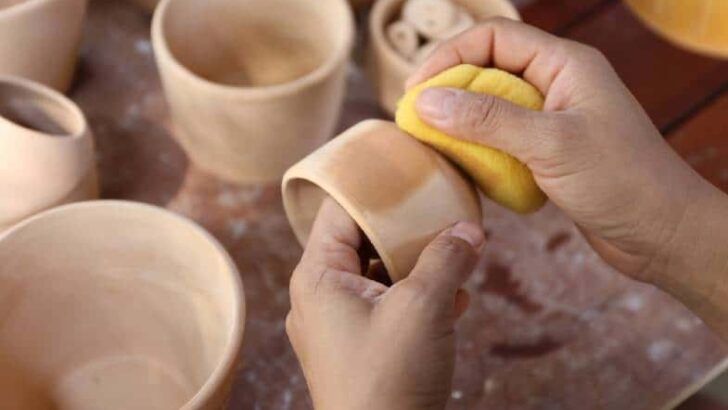

After extracting the clay from local mines, workers soaked it in water pits to make it malleable. They then kneaded the clay thoroughly to remove any air bubbles and impurities. This process produced a smooth, elastic clay ready for sculpting.

Sculpting

The sculpting of the terracotta warriors involved several intricate techniques and processes. The artisans worked in assembly line workshops, each focusing on a particular part of the figure. Some worked on the heads, others on the torsos, arms, legs, etc. Molds were likely used to ensure consistency, but each sculpture was individually worked and customized.

Clay was built up by hand around armatures and frames to shape the bodies. Features were sculpted using a variety of specialized tools made from wood, bamboo and metal. Great attention was given to capturing realistic details like facial expressions, clothing, hairstyles, shoes and gestures. The figures’ ears were made to be slightly oversized so they could better hear orders from the emperor in the afterlife.

The sculpting process required enormous time, labor and skill. It’s estimated that each figure took 10-12 months to complete. Yet despite the challenging work, the artisans achieved an astounding uniformity of quality and design throughout the entire army.

Assembly Line Production

The assembly line was critical to producing over 8,000 terracotta warriors in such a short time. It allowed the sculptures to be mass produced through a division of labor using standardized parts.

Different teams were each assigned a specific task, such as shaping the heads, torsos, arms, legs, etc. This sped up production significantly compared to if a single artisan had to create an entire figure themselves.

Sections of the warriors were pre-fabricated using molds. Things like the armor, hairstyles, shoes, and other accessories were largely identical across figures. This standardization allowed the parts to be rapidly assembled into complete warriors.

Thanks to this almost factory-like system, the terracotta army could be efficiently manufactured in huge numbers. The uniformity of the warriors’ body parts allowed for quick assembly, while custom heads and paint jobs gave each one a unique appearance.

Individualization

While the army of terracotta warriors exhibits remarkable uniformity overall, each sculpture was designed to be unique. The artisans imbued a distinct personality in each warrior through subtle individualized facial features. No two faces are exactly alike – some have round faces, some have skinny faces, some have high cheekbones, some have large eyes. Even details like mustaches, beards, hair buns, and wrinkles were carefully sculpted to differentiate the warriors.

In addition to facial features, other aspects of the warriors were customized as well. The armor design, clothing details, hairstyles, shoes, and even the pleating of the robes exhibit subtle variations. Some warriors have top knots on their hair buns while others do not. Experts estimate the Terracotta Army contains around 10 basic face models, with further alterations made to create diversity. Modern facial recognition technology has identified over 8,000 unique faces among the figures!

The artisans likely worked from a set of master templates but customized each sculpture to maintain uniqueness. This reflected the Chinese philosophy that every individual, no matter how humble, deserved to maintain their distinct identity. The painstaking individualization of each warrior speaks to the immense skill, craftsmanship and manpower that was marshalled to create Emperor Qin’s eternal Terracotta Army.

Coloring

The terracotta warriors were originally painted in bright pigments of red, blue, green, pink, black, brown, white and lilac. The pigments were derived from minerals such as azurite (for blue), malachite (for green), cinnabar (for red) and from carbon (for black). The raw pigments were mixed with water soluble binders like animal glue to create the paints.

The painted surface not only made the warriors more lifelike and individualized, but also protected the clay beneath. The warriors were painted after assembly, and great care was taken even with details like the braided hair and decorations on the armor. The painting was done in an assembly line, with different artisans responsible for different colors. The painters used fine brushes for smaller areas and wider brushes for larger areas. They applied multiple layers of pigments and added black lines as outlines.

Unfortunately, once exposed to air, light and moisture, the original pigments faded quickly. Traces still remain on some figures, giving archaeologists insight into the warriors’ original colorful appearance.

Weapons

The terracotta warriors were buried with real bronze weapons, adding to the realism and uniqueness of each warrior. The bronze weapons were created in specialized workshops near the emperor’s tomb.

The blacksmiths employed advanced techniques to produce high quality bronze blades, arrowheads, and polearms. The weapons were made using the “lost wax” technique which allowed the blacksmiths to create intricate details and patterns.

First, the artisans sculpted the weapons out of clay and coated them with wax to create a model. Next, they applied clay around the wax model to create a mold. The wax was melted and drained out of the mold, leaving a hollow clay shell. Finally, molten bronze was poured into the mold to cast the weapon.

The weapons vary according to the rank and role of each warrior. Higher ranking officers carry ornate swords, halberds, spears, and axes. Cavalrymen wield swords and long lances. Infantrymen carry single-edged swords, polearms, crossbows, and dagger axes. Archers hold real usable composite bows and bolts.

The bronze weapons bristled with sharp edges and exquisite craftsmanship, ready for battle. Their inclusion demonstrates the detail and artistry that went into creating Emperor Qin’s eternal army.

Burial

After the terracotta warriors were completed, they were arranged in battle formation and buried in pits very close to the tomb of Qin Shi Huang, the first emperor of China. This was done to serve as an army and protection force for the emperor in the afterlife. The warriors were buried in three main pits that were quite large in scale.

Pit 1 is the largest and contains around 6,000 terracotta figures, with warriors, horses and chariots arranged in battle formation divided into groups based on rank and duty. Pit 2 is smaller, containing around 1,000 warriors and horses. Pit 3 is the smallest of the pits and contains 72 figures, including generals, advisors and military officers. The figures were buried in the pits along with real weapons like swords, spears, crossbows and arrows that were made of bronze and had become seriously corroded over time.

Archaeologists believe the pits were dug very deep, around 5 meters or more, and then the warriors and weapons were placed inside in meticulous formation according to rank. The pits were then roofed over with wood and mats before being covered over with earth and soil. Drainage systems were also implemented to help protect the warriors underground. The careful burial in such large scale pits directly next to Qin Shi Huang’s tomb demonstrates how the warriors were created to serve and protect the emperor in his planned immortality and afterlife.

Excavation

The Terracotta Army was discovered completely by accident in 1974 by a group of farmers digging a well near the city of Xi’an. The farmers found pieces of pottery, bronze weapons and terracotta fragments. This prompted Chinese archaeologists to investigate the area further.

In 1976, excavations began on the three pits containing the Terracotta Army under the direction of archaeologist Zhao Kangmin. Pit 1 was the first area excavated, unearthing around 600 terracotta warriors and horses. Pit 2 was excavated next, containing cavalry and infantry units along with war chariots. Pit 3 contained the command post of the army, including high-ranking officers and a war chariot. The three pits together contained over 8,000 soldiers, 130 chariots, and 150 cavalry horses.

The excavation was extremely complex due to the fragile nature of the warriors after being buried for over 2,000 years. The terracotta and wood materials had severely deteriorated and fractures were common. Teams of archaeologists worked meticulously to excavate and restore the figures. Chemical treatments and reinforcements were used to preserve the paint and repair broken limbs or weapons. It took over 20 years of excavation work to completely uncover all three pits.

Today, the excavation site has been converted into a museum housing the pits and restored warriors. Ongoing excavation and restoration continues at the site. More figures and artifacts are still being discovered by archaeologists, shedding new light on the massive ancient army created for China’s first emperor over 2,200 years ago.

Legacy

The Terracotta Army has become one of China’s most significant archaeological discoveries and a major tourist attraction. Over 1.5 million people visit the warriors each year. The site was named a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1987, recognizing its outstanding historical, artistic and scientific value.

The warriors provide significant insight into China’s first imperial dynasty, revealing details about military formations, armor, clothing, hairstyles, government bureaucracy, and craft techniques of the Qin era. They demonstrate the power and wealth of the Qin state, as well as the artistic and engineering skills of the artisans who produced such a vast underground army.

Ongoing research aims to further understand the materials, pigments, construction methods, and organization behind the army. Conservation efforts strive to preserve the warriors in stable conditions. The Lintong Museum located near the pits displays reproductions of the warriors and artifacts found on site. The warriors have inspired worldwide fascination, artistic reimaginings, and replicas reminding us of China’s rich cultural heritage.