Why Does Stoneware Crack In The Oven?

Stoneware is a type of pottery that is impermeable to water and durable for daily use. It is vitrified and fired at high temperatures ranging from 1200°C to 1300°C, making it non-porous. The key composition is clay and some type of flux. Popular fluxes for stoneware are feldspar, nepheline syenite, or talc. These fluxes lower the vitrification temperature, allowing the clay to fuse and become non-porous at lower kiln temperatures. While strong and waterproof, stoneware can be susceptible to cracks during the firing process.

Composition of Stoneware

Stoneware is primarily composed of clay, natural fluxes, and silica and is fired to high temperatures. The main ingredient is clay which gives stoneware its plasticity before firing and strength after. Silica, usually in the form of quartz or sand, provides part of the strength, and natural fluxes promote vitrification during the firing process. Fluxes lower the melting temperature of the silica and clay components and allows the stoneware body to become non-porous at lower temperatures.

The key characteristics of a stoneware clay body include:

- Plastic secondary clay for shaping – usually ball clays or fireclays

- Silica (quartz) for strength

- Fluxes like feldspar to promote vitrification

The combination of the clay, silica, and fluxes along with the high kiln temperatures result in the characteristic non-porous, durable nature of stoneware.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stoneware

Firing Process

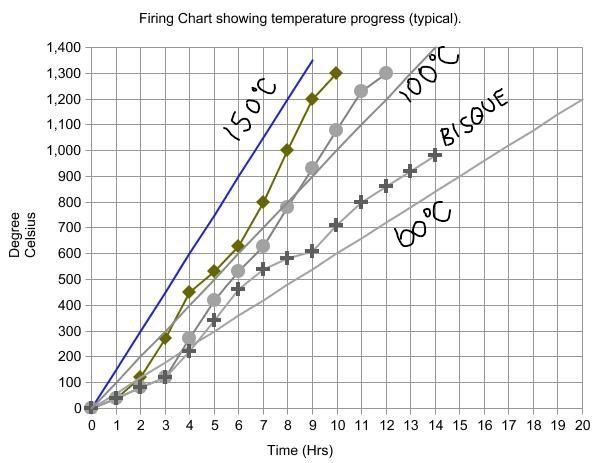

Stoneware clay must be fired at high temperatures, typically between 2,200°F and 2,400°F, to fully vitrify and become a strong, permanent ceramic material. This process, known as vitrification, fuses the clay particles together through sintering and melting, which can only occur at high heat. According to the article “Firing: What Happens to Ceramic Ware in a Firing Kiln” on Digitalfire.com, as the temperature rises in the kiln, fluxes become activated which begin dissolving the quartz particles in the clay body. The clay vitrifies as silica is removed at temperatures generally above 2,200°F.

Most stoneware clay requires a bisque firing followed by a glaze firing. Bisque firing prepares the clay by hardening it slightly and removing water and organic matter between 900-1100°F. Glaze firing melts glass-formers in the glaze onto the clay body to create a glassy coating. This second firing is done between 2,200-2,400°F for stoneware. The specific firing schedule including ramps, holds, and peak temperatures depends on the clay body composition and the glaze chemistry. Firing to the optimal temperature is necessary to properly vitrify stoneware clay into a strong, non-porous ceramic.

Thermal Shock

Thermal shock occurs when there is a rapid change in temperature in the stoneware, causing different parts of the clay to expand and contract at different rates Thermal shock – Digitalfire. This imbalance in expansion puts stress on the molecular structure of the stoneware, which can cause cracks and breakage. The most common causes of thermal shock are placing a cool stoneware piece into a hot oven or removing a hot piece from the oven and placing it on a cold surface.

During the firing process, stoneware undergoes vitrification, where the clay particles and additives fuse together through sintering. If the temperature changes too quickly, the vitrified clay does not have time to adjust to the thermal expansion and its rigid structure is unable to withstand the stress Thermal Shock – ScienceDirect. This results in cracks or fractures through the body of the stoneware. Extreme temperature changes are the main culprit in thermal shock and cracking.

Moisture in Clay

One of the main reasons stoneware may crack while firing is trapped moisture in the clay body. Clay is porous and absorbs water easily. If the clay body is not fully dried before firing, the remaining moisture turns to steam and expands when heated.[1] This expansion puts internal pressure on the clay and can cause cracks and fractures.

Clay minerals such as smectite are highly expansive due to their ability to absorb significant amounts of water molecules between plate-like particle layers. When wet, the clay expands as water is absorbed, and shrinks as it dries, leaving voids in the material.[2] Firing clay with trapped moisture creates a similar expansion effect, which leads to cracks.

To prevent this, it’s crucial to fully dry stoneware before firing to remove all moisture. Slow drying at room temperature is recommended to allow moisture to evaporate from the center outwards and prevent uneven shrinkage stresses. Testing moisture content with a meter before firing will help identify any residual moisture.

Glazes

Glazes play an important role in preventing cracking of stoneware. Glazes and clay have different coefficients of thermal expansion, meaning they expand and contract at different rates as temperatures change during firing. The glaze acts as a protective coating and helps prevent sudden temperature changes in the clay body.

According to Digitalfire, the calculated thermal expansion of a glaze depends on its chemical composition and ingredients like KNaO and SiO2. Glazes with a lower thermal expansion are less likely to crack the clay body underneath during rapid heating or cooling. Using a glaze with a compatible thermal expansion for the specific clay body is crucial.

As explained on Glazy.org, “If the glaze has a much lower thermal expansion than the body, it will craze, creating small cracks that permit water to enter into the clay body. If the glaze has a higher thermal expansion than the body, it will shiver off in flakes during thermal shock” (Glazy).

Testing different glaze recipes and calculating the thermal expansion is important to find the right match for the clay body. The glaze provides a protective layer against sudden temperature changes that lead to cracks.

Preventing Cracks

Cracks in stoneware can happen when a pottery or ceramic piece goes through extremes in temperature. Proper techniques for drying, firing, and cooling can help avoid cracking. Here are some tips for preventing cracks:

Preheat the kiln thoroughly before firing clay pieces. Fast temperature changes are one of the main causes of cracking, so make sure to preheat the kiln to at least 200°F before placing greenware inside. Slowly raise the temperature to the desired cone level based on the clay body and glaze. Do not let temperature fluctuate quickly (Soul Ceramics, Cracks In Pottery).

Choose glazes compatible with the clay body. Glazes and clay materials have different rates of thermal expansion, meaning how much they shrink during firing. Using a glaze that does not fit the clay can lead to cracked glazes. Check manufacturer recommendations and do test tiles before putting finished pieces in the kiln (Zamek – Preventing Cracks).

Allow pieces to cool slowly inside the turned-off kiln. Do not open the kiln door right after firing. Let the internal temperature gradually go down to avoid shocking the clay and glaze materials. Wait until the kiln is below 150°F before removing fired stoneware. Sudden temperature drops make cracking more likely.

Hairline Cracks

Hairline cracks are very small cracks in the glaze of stoneware that often occur during normal use. They are usually caused by the contraction and expansion of the clay body during temperature changes (American Ceramic Society). These tiny cracks do not typically affect the usability or safety of stoneware dishes, but some precautions should still be taken.

Although hairline cracks create small crevices where bacteria can potentially grow, thorough cleaning and drying should prevent this. As long as stoneware with hairline cracks is not soaked or left wet for extended periods, it should be safe to use. However, it is not recommended to store moist foods or liquids in stoneware with cracks for long periods, as noted on Reddit (https://www.reddit.com/r/Ceramics/comments/18265fn/tiny_hairline_cracks_in_a_ceramic_plate_is_it/).

For regular daily use, it is generally considered safe to keep using stoneware with minor hairline cracking, according to most ceramic experts. However, cracked items may be more fragile and prone to further cracking. Heavily cracked stoneware is best avoided for serving food.

Repairing Cracks

There are a few methods for repairing cracks in stoneware. One traditional Japanese technique is called kintsugi, which involves mixing a natural lacquer with powdered gold, silver, or platinum. The lacquer is used to glue the broken pieces back together, and the powdered metal creates veins of shimmering gold or silver that highlights the cracks and repairs1. Kintsugi treats the damage and repair as part of the history of the object rather than something to disguise.

For simpler repairs at home, you can use instant adhesive or epoxy to mend cracks and chips. Start by thoroughly cleaning the area with rubbing alcohol to remove any dirt or oils. Apply a small amount of adhesive or epoxy and press the pieces tightly together for about 10-15 minutes until set. Be sure to use an adhesive rated for high temperatures. After the repair has cured, you may want to use a ceramic filler putty to smooth over the seam2. Sand and finish the area to help blend the repair.

For hairline cracks, you can rub colored wax into the fissure to help disguise it. Beeswax or crayon can be melted and rubbed into the crack with a cloth. Choose a wax color that matches the stoneware. The wax fills and masks thin cracks in the surface.

Conclusion

Stoneware is a durable type of pottery that is popular among artisans and homeowners alike for its aesthetic appeal and functionality. However, it can be susceptible to cracking during the firing process in the kiln or when exposed to sudden temperature changes during use. This is often due to thermal shock, the rapid expansion and contraction of the clay body, as well as trapped moisture in the clay or issues with the glaze.

To prevent cracking, proper drying and bisque firing are essential to remove all moisture before the glaze firing. Glazes should be carefully selected to complement the clay body and have similar expansion rates. Slowly increasing kiln temperatures and providing adequate air circulation allows the stoneware to withstand thermal shock. Hairline cracks may still occur but often do not affect structural integrity. Severe cracks can sometimes be repaired through methods like kintsugi. With care taken during production and use, stoneware can better maintain its signature hearty, durable nature.

In summary, cracking can be minimized by understanding the science behind clay composition, glazes, and the effects of heat. With careful drying, glaze selection, and firing practices, stoneware pottery can better retain its beauty and function.